#19: The Banu Qurayza Incident: Genocide or Justice? Understanding a Contested Moment in Islamic History

Confronting the Hard Questions About Islam, Volume 1

Dear Readers, Those of you who follow my writing know that I typically adopt an exploratory, conversational style in my posts, often raising questions and examining topics through multiple lenses as we journey together through complex ideas. However, the subject I'm addressing today—the Banu Qurayza incident of 627 CE—warrants a more formal, structured approach.

"Was Muhammad a genocidal warlord who massacred Jews? Did early Islam spread through violence and religious persecution? Does Islam promote the indiscriminate execution of non-Muslims?" These accusations represent some of the most severe attacks leveled against Islam and its Prophet, and they often center around the Banu Qurayza incident.This event is frequently cited in discussions about early Islamic history, often extracted from its historical context and presented through a modern ethical lens without proper consideration of the legal, political, and social frameworks of 7th century Arabia. Given the gravity of this topic and its continued relevance to discussions about Islamic justice and governance, I've chosen to present a more comprehensive, academic analysis that draws upon primary sources and modern scholarly consensus.

What follows is the first installment in my new series, "Confronting the Hard Questions About Islam," where I tackle the most challenging accusations and misconceptions about Islamic history, theology, and practice with intellectual honesty and scholarly rigor. This historical research paper examines the Banu Qurayza incident with chronological coherence and contextual depth. While this represents a departure from my usual writing style, I believe the subject matter demands this level of careful analysis and documentation.

I welcome your thoughts and questions on this exploration of a complex historical event that continues to shape perceptions of Islamic history and jurisprudence.

The historical research paper follows below

Abstract

The trial and sentencing of Banu Qurayza (627 CE) remains one of the most contested events in early Islamic history, frequently cited by critics as evidence of Islamic militarism and religious intolerance. However, a thorough historical, legal, and comparative analysis reveals that the incident must be understood within its proper historical and legal context rather than through modern moral frameworks. This paper argues that the punishment of Banu Qurayza was a legal response to wartime treason, not religious persecution, and was consistent with prevailing legal norms across pre-modern civilizations.

Drawing upon primary sources (Ibn Ishaq, Al-Tabari, Ibn Hisham) and contemporary scholarship (Montgomery Watt, Reuven Firestone, Jonathan Brown, Bernard Lewis), this study demonstrates that: (1) The Prophet Muhammad did not personally pass judgment on Banu Qurayza; (2) The tribe chose Sa'd ibn Mu'adh as their arbitrator, who ruled according to Jewish law (Deuteronomy 20:10-14); (3) The ruling was consistent with wartime justice in pre-modern legal traditions; and (4) Islamic governance, when applied holistically, maintains a commitment to justice, restraint, and ethical conduct.

1. Introduction: The Misrepresentation of the Banu Qurayza Incident

The trial and execution of Banu Qurayza's men in 627 CE has become a focal point in critiques of early Islamic history. Critics frequently allege that this incident demonstrates Islam's propensity for indiscriminate mass executions, revenge-based justice, and inherent religious intolerance. These accusations, however, fail to account for crucial historical and legal realities that shaped this event.

The allegations against the Prophet Muhammad and early Islamic governance regarding this incident overlook several critical factors: the historical context of Medina's governance structure and the Constitution of Medina; the documented pattern of treaty violations by Jewish tribes in Medina; the application of Jewish law in determining the punishment; and the comparative historical context of wartime justice in pre-modern civilizations.

This study critically examines primary historical sources, including the accounts of Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Hisham, and Al-Tabari, alongside secondary scholarship from Montgomery Watt, Wael Hallaq, Jonathan Brown, Reuven Firestone, Bernard Lewis, and Fred Donner, to provide a balanced academic perspective on this contentious historical episode. Scholarly interpretation of this incident remains contested, with traditional and revisionist perspectives offering substantially different accounts of both the scale and nature of the punishment. While conventional narratives suggest widespread execution of combatants, recent critical scholarship has questioned both the reliability of these accounts and their consistency with the Prophet's documented approach to justice and conflict resolution. This study examines these competing interpretations to present a more nuanced understanding of this complex historical event.

The Banu Qurayza incident cannot be properly understood without situating it within the broader political landscape of 7th century Arabia. Prior to the Prophet Muhammad's arrival in Medina, the city was characterized by tribal fragmentation and ongoing conflicts between its major Arab tribes, Aws and Khazraj, with the three Jewish tribes—Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza—often playing pivotal roles in these disputes through strategic alliances. This volatile political environment, particularly in the aftermath of the devastating Battle of Bu'ath (617 CE), created the conditions that led to Muhammad's invitation to Medina as a neutral arbitrator.

Within this context, the Constitution of Medina (Meesaq-e-Medina) established a legal framework that guaranteed religious freedom while creating mutual obligations for all communities. Among these obligations was the commitment to collective defense and the prohibition of secret alliances with external enemies threatening Medina's security. The treaty violations by the Jewish tribes, culminating in Banu Qurayza's conspiracy with Quraysh during the Battle of the Trench, represented not religious dissent but political treason during a time of existential threat to the entire community.

This paper will systematically address the historical distortions surrounding the Banu Qurayza incident by examining the primary sources, analyzing the legal basis for the judgment, comparing the ruling with other pre-modern and modern legal precedents for treason, and situating the event within the broader context of Islamic ethical principles of governance and justice. Through this comprehensive approach, we can move beyond polemical interpretations to reach a more nuanced understanding of this complex historical event.

2. The Political and Social Context of Pre-Islamic Medina

To understand the Banu Qurayza incident, one must first examine the socio-political landscape of Medina before Islam's arrival. Pre-Islamic Medina was a fragmented society plagued by tribal warfare and political instability, lacking any centralized governing authority.

The city was primarily dominated by two major Arab tribes, Aws and Khazraj, who were locked in perpetual feuds and power struggles. Alongside these Arab tribes were three influential Jewish tribes: Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza, who controlled significant economic resources and agricultural lands. This tribal configuration created a volatile political environment where alliances shifted frequently, and no single authority could maintain peace.

The Battle of Bu'ath (617 CE), a devastating conflict between Aws and Khazraj that involved their respective Jewish allies, left Medina severely weakened and vulnerable to external threats. This prolonged tribal warfare drained the city's resources and undermined its security, creating an urgent need for political stability. As Montgomery Watt (1956, p. 133) notes, the battle's aftermath left Medina with "no clear dominant power" and generated recognition among tribal leaders that "continued warfare would lead to the city's complete collapse."

Recognizing the need for a neutral arbitrator who could unify these fractured tribes, the leaders of Medina extended an invitation to the Prophet Muhammad to serve as an impartial mediator. This invitation came through two significant meetings known as the First and Second Pledges of Aqabah (621-622 CE), culminating in Muhammad's migration (Hijrah) to Medina in 622 CE.

This historical context reveals that the Prophet Muhammad was invited to Medina specifically because of his reputation for justice and honesty. He did not arrive as a conqueror but as a requested arbitrator tasked with establishing peace among warring factions. This foundational reality challenges narratives that portray early Islamic governance in Medina as an imposed theocracy rather than a consensual political arrangement.

2.1 Tribal and Political Structure of Pre-Islamic Medina

Medina's pre-Islamic society was primarily structured around tribal affiliations, which dictated political alliances, economic power, and security. The city's two dominant Arab tribes, Aws and Khazraj, were often in conflict, while the Jewish tribes controlled key economic resources, such as agriculture and trade (Donner, 2010).

The Aws and Khazraj were descendants of the Qahtani Arab lineage, originating from Yemen. They migrated to Yathrib (later renamed Medina) centuries before Islam, establishing settlements and engaging in agricultural practices (Ibn Hisham, 1955, p. 210). However, over time, political tensions between the two tribes escalated into open warfare.

The Aws aligned with some Jewish tribes, particularly Banu Qurayza, to strengthen their military position. Meanwhile, the Khazraj had a fluctuating relationship with Jewish tribes, often shifting allegiances based on economic and military advantage (Watt, 1956, p. 128). Although inter-tribal marriages and trade agreements existed, the dominant political landscape of pre-Islamic Medina was one of rivalry, power struggles, and shifting alliances (Lewis, 1984).

2.2 The Jewish Tribes: Economic and Strategic Power

The Jewish presence in Medina dated back several centuries. They were considered People of the Book (Ahl al-Kitab) and had distinct religious and legal customs that differentiated them from the polytheistic Arabs (Firestone, 1999). The three major Jewish tribes exercised considerable influence through their economic activities:

Banu Qaynuqa were skilled in craftsmanship, particularly goldsmithing and blacksmithing, controlling much of the artisanal production in the city. Banu Nadir were wealthy landowners who controlled large portions of Medina's date palm orchards, giving them significant agricultural power. Banu Qurayza were known for their fortified settlements and military alliances, providing them with strategic advantage.

Unlike the Arab tribes, the Jewish tribes did not operate as a unified bloc—they often allied with either Aws or Khazraj for strategic purposes (Hawting, 2000, p. 56). This fragmentation meant that they lacked political dominance over the region despite their economic influence.

2.3 Medina's Governance: A Stateless Society

Medina lacked a centralized governing authority before Islam. Unlike Mecca, which was controlled by the Quraysh through the Dar al-Nadwa (Council of Nobles), Medina functioned as a loosely structured tribal confederation, where disputes were settled through inter-tribal agreements, retaliatory justice, or temporary military coalitions (Watt, 1956, p. 131).

This decentralized system allowed tensions to escalate unchecked, leading to full-scale tribal warfare. Without formal institutions for conflict resolution, blood feuds and revenge killings perpetuated cycles of violence that destabilized the entire region.

2.4 The Battle of Bu'ath: A Turning Point in Medina's Political Crisis

The Battle of Bu'ath in 617 CE represented the culmination of decades of hostility between Aws and Khazraj. This devastating conflict drained Medina's resources and weakened all its factions, creating the conditions that would eventually lead to the invitation extended to Prophet Muhammad.

The causes of this conflict included disputes over trade and agricultural resources (Lewis, 1984), a cycle of revenge killings between Aws and Khazraj (Hawting, 2000, p. 44), and Jewish political maneuvering, as different Jewish factions supplied arms and financial backing to competing Arab groups (Donner, 2010, p. 178).

During the battle, the Aws formed an alliance with Banu Qurayza, while the Khazraj received support from Banu Nadir. Hundreds were killed, including several leading tribal chiefs. The Khazraj suffered significant losses, reducing their influence over Medina's affairs.

The battle left Medina politically unstable and created three major problems: no clear dominant power emerged as both Aws and Khazraj were militarily weakened; Jewish tribes increased their economic and political leverage; and the need for an impartial mediator became evident, as both Aws and Khazraj recognized that continued warfare would lead to the city's complete collapse (Watt, 1956, p. 133).

2.5 The Invitation to the Prophet Muhammad

By 621 CE, the leaders of Aws and Khazraj realized that their internal conflicts had left Medina vulnerable to external threats, particularly from the Quraysh of Mecca. They sought an external arbitrator who was politically neutral, respected for his wisdom and justice, and able to unify the fractured tribes.

The First Pledge of Aqabah in 621 CE saw a delegation of six leaders from Khazraj travel to Mecca, where they met the Prophet Muhammad and invited him to Medina. They recognized his reputation for honesty and justice, even before his prophethood (Donner, 2010, p. 92), and pledged their allegiance to him as a leader and sought his arbitration in Medina's affairs.

The Second Pledge of Aqabah in 622 CE involved a larger delegation of 75 representatives from both Aws and Khazraj who met the Prophet in Mecca and reaffirmed their commitment: "We will obey you in matters of peace and war. We will defend you as we defend our own families" (Ibn Hisham, 1955, p. 287). This formalized the agreement for the Prophet to migrate to Medina and serve as its political leader.

This historical context is crucial for understanding that Muhammad entered Medina not as a military conqueror but as an invited mediator, tasked with establishing peace in a deeply divided society. The subsequent Constitution of Medina would represent his first major political achievement in transforming this fragmented tribal society into a cohesive political entity with defined rights and responsibilities for all its members..

3. The Constitution of Medina: A Legal Framework for Coexistence

Upon migration to Medina, one of the Prophet Muhammad's first acts was drafting the Meesaq-e-Medina (Constitution of Medina), a pioneering legal charter that established a framework for peaceful coexistence among Medina's diverse religious and tribal communities. This document represents one of the earliest recorded written political constitutions in history and laid the groundwork for a pluralistic society under a unified governance structure.

The Constitution of Medina contained over fifty clauses addressing political, legal, religious, and security matters (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 252). It established Medina as a single political entity (Ummah) while simultaneously guaranteeing religious autonomy for its diverse inhabitants. As stated in the document: "The Jews have their religion, and the Muslims have theirs. Each community is responsible for its own affairs" (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 253).

This constitutional framework included several key provisions that would later become relevant to the Banu Qurayza incident. First, it guaranteed religious freedom and legal autonomy for all communities, allowing Jewish tribes to maintain their religious practices and internal laws. Second, it established a mutual defense pact that obligated all signatories to defend Medina against external threats. Third, and most crucially, it explicitly prohibited secret alliances with external enemies that might undermine Medina's collective security.

The Constitution provided a legal mechanism for addressing violations of these provisions, establishing the Prophet Muhammad as the final arbitrator in disputes. As Wael Hallaq (2009, p. 103) observes, this document created "a binding social contract that recognized the diverse religious communities of Medina while creating a unified legal-political structure."

The significance of the Constitution of Medina extends beyond its historical context. It established a precedent for religious pluralism under a single governance system (Armstrong, 1991, p. 127) and demonstrates that early Islamic governance recognized and protected the rights of non-Muslim communities. Furthermore, it refutes claims that Islam imposed conversion by force, as it explicitly guaranteed religious freedom for all inhabitants of Medina.

The Constitution's provisions regarding treason and external alliances would become particularly relevant during the Battle of the Trench (627 CE), when Banu Qurayza's actions directly violated their constitutional obligations.

3.1 Historical Background: Why Was a Constitution Needed?

Following the Battle of Bu'ath (617 CE), Medina was in political disarray, with no centralized authority to enforce laws or settle disputes (Watt, 1956, p. 133). The invitation of the Prophet Muhammad as an arbitrator (621-622 CE) led to the migration (Hijrah) of Muslims to Medina (622 CE) and created the need for a formal political structure to govern the city.

Before the Prophet's arrival, Medina was governed by tribal customary law, which was decentralized, with each tribe having its own laws; retaliatory, as justice was based on revenge (e.g., blood feuds); and ineffective in preventing conflicts, as there was no impartial authority to mediate disputes (Donner, 2010, p. 95).

Upon assuming leadership, the Prophet Muhammad sought to establish Medina as a structured polity, where all inhabitants were protected under a common legal framework, laws applied to both Muslims and non-Muslims equally, and security, trade, and justice were centralized under a single system. This resulted in the drafting of the Constitution of Medina, a binding social contract that recognized the diverse religious communities of Medina while creating a unified legal-political structure (Hallaq, 2009, p. 103).

3.2 Key Clauses of the Constitution of Medina

3.2.1 Establishing Medina as a Single Political Entity (Ummah)

"This is a document from Muhammad, the Prophet, between the believers and the Jews. They are one Ummah (nation), distinct from others." (Ibn Hisham, 1955, p. 289).

The significance of this clause was profound. It defined Medina as a single political unit, irrespective of religious differences; unified previously warring factions (Aws, Khazraj, and Jewish tribes); and created a precedent for religious pluralism under a single governance system (Armstrong, 1991, p. 127).

3.2.2 Religious Freedom and Legal Autonomy

"The Jews have their religion, and the Muslims have theirs. Each community is responsible for its own affairs." (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 253).

This clause guaranteed religious freedom, allowing Jews and pagans to retain full control over their faith, and established legal autonomy, as Jewish and Arab tribes had separate internal laws (Hawting, 2000, p. 77). This principle aligns with the Qur'anic verse (2:256): "There is no compulsion in religion," demonstrating that the Prophet Muhammad did not impose Islamic law upon non-Muslims, countering claims that Islam enforced conversion by force.

3.2.3 Collective Defense Against External Threats

"If anyone attacks Medina, all its inhabitants—Muslims and Jews—must fight together in its defense." (Al-Tabari, 2007, p. 151).

This provision established mutual defense between all communities, prevented individual tribes from making separate pacts with external enemies, and strengthened Medina against threats from Mecca (Quraysh) and surrounding tribes.

3.2.4 Prohibition of Treason and Secret Alliances

"No group shall enter into a separate peace treaty with an enemy, without the consent of Muhammad." (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 256).

This clause was designed to prevent factions from undermining Medina's security and clearly defined treason as a punishable offense. This provision was later violated by Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza, leading to their respective trials and punishments.

3.3 The Legal Precedent of the Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina is recognized as one of the earliest written constitutions in history, a legal contract that predated Western constitutional frameworks (e.g., Magna Carta, 1215 CE), and a model for later Islamic governance, emphasizing justice, security, and religious coexistence (Brown, 2017, p. 219).

3.4 The Violations of the Constitution and Their Consequences

Despite its guarantees of protection and mutual defense, certain Jewish factions later breached the treaty. Banu Qaynuqa insulted and assaulted a Muslim woman in the marketplace (624 CE) and were subsequently expelled from Medina. Banu Nadir plotted to assassinate the Prophet Muhammad (625 CE) and were exiled to Khaybar. Most significantly, Banu Qurayza conspired with Quraysh during the Battle of the Trench (627 CE) and were tried and sentenced for treason.

The Qur'an references these breaches in Surah Al-Anfal (8:58): "If you learn of treachery from a people, respond in kind, but do not be unjust." These violations illustrate that the Constitution was not merely symbolic—it was a binding contract with real consequences (Donner, 2010, p. 188).

The Constitution of Medina thus established a legal framework for Medina's multi-religious society, guaranteed religious freedom while defining obligations for all communities, introduced laws against treason and external alliances, and became the precedent for later Islamic governance. This context is essential for understanding the legal basis upon which subsequent actions, including the judgment against Banu Qurayza, would be founded.

4. The Systematic Treachery of Banu Qurayza and Other Jewish Tribes

Following the establishment of the Constitution of Medina, a pattern of treaty violations emerged among certain Jewish tribes. These breaches were not isolated incidents but represented a systematic undermining of Medina's security during critical moments of vulnerability.

The first significant violation came from Banu Qaynuqa in 624 CE, following the Muslims' victory at the Battle of Badr. According to Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 357), members of this tribe publicly humiliated a Muslim woman in the marketplace, leading to a violent confrontation in which a Muslim man was killed. When the Prophet Muhammad attempted diplomatic negotiations, Banu Qaynuqa rejected reconciliation and openly challenged Muslim authority. After a two-week siege, they surrendered and were exiled to Khaybar rather than executed, demonstrating the Prophet's preference for exile over capital punishment when possible.

The second major treaty violation came from Banu Nadir in 625 CE, following the Muslims' defeat at the Battle of Uhud. When the Prophet Muhammad visited their stronghold to negotiate a blood-money settlement for a separate matter, they conspired to assassinate him by dropping a large rock on him from above (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 366). Upon discovery of this plot, they were ordered to leave Medina. After initially refusing and preparing for conflict, they eventually surrendered and were allowed to take their wealth and resettle in Khaybar.

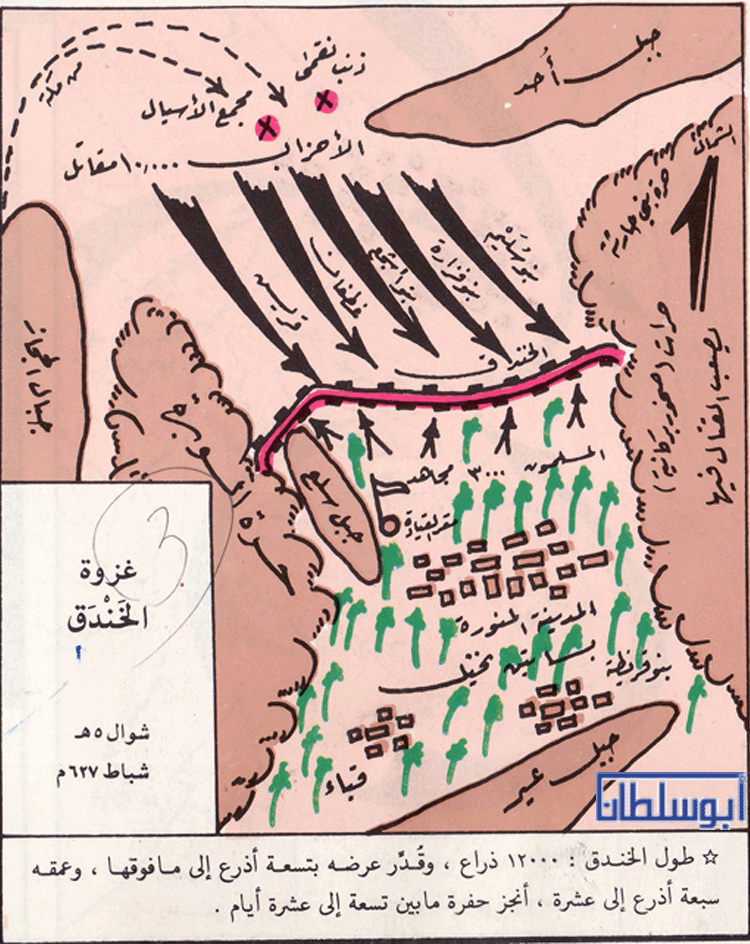

The most serious breach occurred during the Battle of the Trench (627 CE), when Medina faced an existential threat from a Quraysh-led coalition of 10,000 troops. Despite their constitutional obligation to defend the city, Banu Qurayza instead secretly negotiated with the attacking forces. Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 394) records that Banu Qurayza's leaders met with envoys from Quraysh and agreed to attack Muslims from within the city while Quraysh forces attacked from outside. This coordinated pincer attack would have likely resulted in the complete destruction of Medina had it succeeded.

The Qur'an references this betrayal in Surah Al-Ahzab (33:26): "And He brought down those who supported them among the People of the Book from their fortresses, and cast terror into their hearts—a group you killed, and others you took captive."

This pattern of treaty violations demonstrates that the conflict with Banu Qurayza was not religiously motivated but was instead a response to specific acts of political betrayal. Each tribe had willingly entered into the Constitution of Medina, acknowledging its provisions regarding mutual defense and prohibition of secret alliances with enemies. Their subsequent violations represented not religious dissent but political treason during times of war.

4.1 Banu Qaynuqa (624 CE): Economic Dominance and Market Conflict

4.1.1 Background: Banu Qaynuqa's Economic and Political Influence

Banu Qaynuqa, a Jewish tribe living in Medina, specialized in goldsmithing, blacksmithing, and armor production. They were economically powerful, maintaining influence through trade and alliances with the pagan Arab factions (Lewis, 1984, p. 97).

Though they signed the Constitution of Medina, which guaranteed mutual protection and non-aggression, tensions arose due to their economic control over Medina's market, their opposition to Islam's rise, fearing loss of influence, and their indirect support for Meccan (Quraysh) interests (Donner, 2010, p. 141).

4.1.2 The Incident: Assault on a Muslim Woman and Retaliatory Killing

In 624 CE, after the Muslims' victory in the Battle of Badr, tensions between Banu Qaynuqa and the Muslim community escalated. Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 357) records:

A Muslim woman entered a marketplace controlled by Banu Qaynuqa to purchase goods.

A Jewish merchant publicly humiliated her by tying her dress to a post, exposing her.

A Muslim man intervened to defend her but was killed by Banu Qaynuqa's allies.

A cycle of retaliation ensued, escalating into an armed confrontation.

4.1.3 Political Consequences: Expulsion, Not Execution

Given the escalating conflict, the Prophet Muhammad attempted diplomatic negotiations, urging Banu Qaynuqa to remain loyal to the Constitution. They rejected reconciliation and openly challenged Muslim authority, daring the Prophet to fight them (Ibn Hisham, 1955, p. 314). A two-week siege ensued, after which they surrendered. Instead of execution, they were exiled to the Jewish stronghold of Khaybar.

The Qur'an reflects on this in Surah Al-Anfal (8:58): "If you learn of treachery from a people, respond in kind, but do not be unjust."

4.1.4 Legal and Historical Parallels

There were clear precedents for this action in Jewish Law, as Deuteronomy 17:2-5 prescribes exile or execution for treason. Similarly, exile was a standard punishment for violating alliances in Arabian Tribal Law. The Islamic response showed leniency, as Banu Qaynuqa were allowed to leave with their wealth, showing mercy compared to pre-Islamic practices (Brown, 2017, p. 204).

4.2 Banu Nadir (625 CE): Assassination Plot Against the Prophet

4.2.1 Background: Banu Nadir's Wealth and Political Ambitions

Banu Nadir controlled vast agricultural lands and date orchards. Initially, they maintained neutral relations with Muslims but feared that Islam's growing influence would reduce their political autonomy (Firestone, 1999, p. 176).

4.2.2 The Assassination Conspiracy

In 625 CE, after the Muslims' defeat at Uhud, tensions increased. The Prophet Muhammad visited Banu Nadir's stronghold to negotiate a blood-money settlement, but they secretly plotted to assassinate him by dropping a rock on him (Ibn Ishaq, 1998, p. 366).

4.2.3 Consequences: Exile to Khaybar, Not Massacre

Upon discovering the plot, the Prophet Muhammad ordered Banu Nadir to leave Medina. They refused and prepared for war, but after a brief siege, they surrendered. They were allowed to take their wealth and settle in Khaybar (Lewis, 1984, p. 110).

The Qur'an addresses this event in Surah Al-Hashr (59:2-3): "It is He who expelled those among the People of the Book who disbelieved. Had it not been for Allah's decree, they would have been destroyed."

From a legal perspective, attempted assassination of a state leader warranted exile or execution under Arabian and Jewish laws (Donner, 2010, p. 187).

4.3 Banu Qurayza (627 CE): Wartime Treason

4.3.1 The Battle of the Trench (627 CE): Medina Under Siege

During the Battle of the Trench (627 CE), Quraysh besieged Medina with 10,000 troops. The city's survival depended on internal unity. Banu Qurayza, bound by the Constitution of Medina, were obligated to defend the city. Instead, they secretly conspired with Quraysh to attack Muslims from behind (Ibn Hisham, 1955, p. 342).

Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 394) records that a secret envoy from Quraysh met with Banu Qurayza's leaders, urging them to betray Medina. Banu Qurayza agreed, violating the Constitution. The siege lasted 27 days before the Muslims repelled the Quraysh attack.

4.3.2 The Trial and Sentencing

Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 402) reports: "When Banu Qurayza surrendered, they requested Sa'd ibn Mu'adh—an ally—to decide their fate."

Sa'd ruled according to Jewish law (Deuteronomy 20:10-14), which prescribed execution for treason. Only the fighting men (combatants) were executed; women and children were spared. This was a legal judgment under their own tradition, not an arbitrary massacre.

The Qur'an reflects on this event in Surah Al-Ahzab (33:26): "And He brought down those who supported them among the People of the Book, casting terror into their hearts. Some you killed, and others you took captive."

This ruling had clear legal precedent: Deuteronomy 20:10-14 mandates execution for wartime betrayal, Roman and medieval European laws treated treason similarly, and in the modern era, post-WWII France executed Nazi collaborators for treason.

4.4 Understanding the Pattern of Betrayals

The pattern of violations by the three Jewish tribes in Medina shows an escalation in both the severity of the breaches and the corresponding punishments:

Banu Qaynuqa's attack on civilians led to expulsion.

Banu Nadir's assassination plot led to exile.

Banu Qurayza's wartime betrayal, the most serious offense as it threatened the entire city, led to trial and execution.

This progression demonstrates that the punishments were proportional to the crimes committed, following established legal practices of the time, rather than being arbitrary or religiously motivated. The focus was consistently on the political crime of treason rather than on religious identity, as evidenced by the fact that other Jewish tribes who honored the Constitution continued to live peacefully in Medina.

4.5 Critical Reappraisal of Traditional Narratives

Recent scholarship has challenged conventional accounts of the Banu Qurayza incident, offering alternative interpretations that warrant consideration. According to a 2022 study published in the Islamic Sciences Journal, traditional narratives about the scale and nature of punishments may contain significant exaggerations and inconsistencies.

4.5.1 Questioning the Casualty Numbers

While traditional sources cite between 400-900 executed men, critical scholars have questioned the plausibility of these figures. As noted by Sah Rabih Situn Nadir and Ismail Mohammed Jalal (2022), "The total population of Medina at that time could not have supported such large numbers from a single tribe." Their analysis suggests that only the principal conspirators—approximately nine individuals identified as tribal leaders who orchestrated the betrayal—faced execution rather than the entire male population.

This alternative reading aligns with what we know about the Prophet Muhammad's general preference for clemency and his previous handling of similar situations with Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir, where exile rather than execution was the prescribed punishment despite serious transgressions.

4.5.2 Source Critical Analysis

The traditional narrative relies heavily on accounts compiled decades or even centuries after the events. Ibn Ishaq's biography, our earliest substantial source, was written approximately 150 years after the Prophet's death and contains narratives from Jewish converts whose objectivity may be questioned given their tribal affiliations.

Critical analysis of transmission chains (isnad) reveals potential weaknesses in how these accounts were preserved and transmitted. The 2022 study highlights that many narrations trace back to individuals like Atiyyah al-Qurazi, whose reliability has been questioned by hadith scholars. Furthermore, the accounts contain internal contradictions regarding crucial details such as the duration of the siege (variously reported as 15, 25, or 27 days) and the conditions under which surrender occurred.

4.5.3 Quranic Context and Textual Evidence

The Quranic references to this incident notably lack explicit mention of mass executions. Surah Al-Ahzab (33:26) states: "And He brought down those who supported them among the People of the Book from their fortresses and cast terror into their hearts. A group you killed, and you took a group captive." The phraseology "a group" (farīqan) rather than "all men" potentially supports the view that punishment was limited to the principal conspirators rather than the entire male population.

This reading would be consistent with the Qur'anic emphasis on proportionality in punishment and the principle articulated in Surah Al-Ma'idah (5:32) regarding the sanctity of human life.

4.5.4 Historical Context of Sa'd's Judgment

Critical scholarship has also noted the physical and psychological state of Sa'd ibn Mu'adh when rendering his judgment. Having been mortally wounded during the Battle of the Trench, Sa'd was in severe pain and near death—conditions that may have influenced his decision. Some accounts suggest he had explicitly prayed to live long enough to witness retribution against Banu Qurayza, potentially indicating a predetermined bias in his judgment.

4.5.5 Integration with Broader Historical Patterns

The revisionist interpretation better aligns with the Prophet Muhammad's documented pattern of political pragmatism and preference for reconciliation when possible. Throughout his leadership in Medina, he consistently sought to build alliances rather than eliminate opponents, as evidenced by his treatment of Meccan leaders following their surrender. A targeted punishment of the primary conspirators rather than wholesale execution would be more consistent with this established pattern.

4.6 Primary Hadith Sources on the Banu Qurayza Incident

A thorough understanding of the Banu Qurayza incident requires examination of authentic hadith sources that document different aspects of this historical event. The following narrations from respected collections provide crucial context for both the sequence of events and their religious and legal significance.

4.6.1 The Prophet's Order to March to Banu Qurayza

In Sahih al-Bukhari, Ibn Umar narrates:

"The Prophet said to us when he returned from the Battle of the Trench (al-Ahzab): 'None of you should pray the afternoon ('Asr) prayer except at Banu Qurayza.'"

روى البخاري في صحيحه عن ابن عمر - رضي الله عنه - قال: قال النبي ﷺ لنا لما رجع من الأحزاب: «لا يصلين أحد العصر إلا في بني قريظة»

This hadith illustrates the urgency with which the Prophet Muhammad addressed the Banu Qurayza situation immediately following the Battle of the Trench. Some Companions interpreted this order literally and delayed their prayer until reaching Banu Qurayza, while others understood it as an instruction to hurry and prayed on the way. This difference in interpretation demonstrates the companions' diverse approaches to textual understanding, foreshadowing later developments in Islamic jurisprudence regarding literal versus contextual readings of religious instructions.

4.6.2 Gabriel's Directive After the Battle of the Trench

Aisha narrates in Sahih al-Bukhari:

"When the Messenger of Allah returned on the day of the Trench and laid down his arms and bathed, Gabriel came to him with his head covered in dust, and said: 'You have laid down your arms? By Allah, I have not laid mine down.' The Messenger of Allah said: 'Where to?' He pointed towards Banu Qurayza. So the Messenger of Allah went out to them."

روى البخاري في صحيحه عن عائشة - رضي الله عنها- قالت: إن رسول الله ﷺ لما رجع يوم الخندق ووضع السلاح، واغتسل فأتاه جبريل وقد عصب رأسه الغبار، فقال: وضعت السلاح فوالله ما وضعته، فقال رسول الله ﷺ: «فأين» قال، ها هنا، وأومأ إلى بني قريظة، قالت: فخرج إليهم رسول الله ﷺ

This narration establishes the divine directive behind the Prophet's action against Banu Qurayza, indicating that this was not merely a political or military decision but one with spiritual significance. The angelic instruction emphasizes the severity of Banu Qurayza's betrayal and positions the response as a divinely sanctioned action rather than a personal vendetta.

4.6.3 Sa'd ibn Mu'adh's Judgment

Abu Sa'id al-Khudri reports in Sahih al-Bukhari:

"When Banu Qurayza surrendered accepting the judgment of Sa'd ibn Mu'adh, the Messenger of Allah sent for him. He came riding a donkey, and when he approached, the Messenger of Allah said: 'Stand up for your leader.' He came and sat beside the Messenger of Allah, who said to him: 'These people have accepted your judgment.' He said: 'I judge that their fighters should be killed and their women and children taken captive.' The Prophet said: 'You have judged according to the King's judgment.'"

روى البخاري في صحيحه عن أبي سعيد الخدري - رضي الله عنه - ، قال: لما نزلت بنو قريظة على حكم سعد هو ابن معاذ، بعث رسول الله ﷺ وكان قريبا منه، فجاء على حمار، فلما دنا قال رسول الله ﷺ: «قوموا إلى سيدكم» فجاء، فجلس إلى رسول الله ﷺ، فقال له: إن هؤلاء نزلوا على حكمك، قال: فإني أحكم أن تقتل المقاتلة، وأن تسبى الذرية، قال: (لقد حكمت فيهم بحكم الملك)

This hadith is particularly significant as it establishes several crucial facts: Banu Qurayza themselves chose Sa'd as their arbitrator; the judgment distinguished between combatants and non-combatants; and the Prophet confirmed that Sa'd's judgment aligned with divine justice (referred to as "the King's judgment"), indicating accordance with Jewish law as elaborated in Section 5.2 of this study.

4.6.4 Identification of Pubescent Males

Atiyyah al-Qurazi, who was himself among the captives, narrates in Sunan Al-Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud, Al-Nasa'i, and Ibn Majah:

"I was among the captives of Banu Qurayza. They examined us, and those who had grown pubic hair were executed, while those who had not were spared. I was among those who had not grown hair."

روى كل من الترمذي، وأبي داود، والنسائي، وابن ماجة عن عطية القرظي - رضي الله عنه- قال: (كنت من سبي بني قريظة، فكانوا ينظرون، فمن أنبت الشعر قتل، ومن لم ينبت لم يقتل، فكنت فيمن لم ينبت)

This first-hand account from a survivor provides crucial insight into how combatants were distinguished from non-combatants. Physical maturity (determined by pubic hair growth) was used as the criterion for identifying those considered adult men capable of participating in combat versus those considered minors. This demonstrates that the punishment was not indiscriminate but followed established legal principles regarding criminal responsibility based on physical maturity.

4.6.5 The Female Captive Who Was Executed

Aisha narrates in Sunan Abu Dawud:

"No woman among them (Banu Qurayza) was killed except one. She was with me, talking and laughing heartily while the Messenger of Allah was killing her men with swords. Suddenly a caller called her name: 'Where is so-and-so?' She said: 'I am here.' I asked: 'What is the matter with you?' She said: 'I did something.' She was taken away and beheaded. I will never forget how surprised I was that she was laughing excessively, although she knew that she would be killed."

روى أبو داود في كتابه السنن عن عائشة- رضي الله عنها- قالت: "لم يقتل من نسائهم - تعني بني قريظة - إلا امرأة، إنها لعندي تحدث تضحك ظهرا وبطنا ورسول الله ﷺ يقتل رجالهم بالسيوف، إذ هتف هاتف باسمها أين فلانة؟ قالت: أنا. قلت: «وما شأنك؟» قالت: حدث أحدثته. قالت: «فانطلق بها فضربت عنقها، فما أنسى عجبا منها أنها تضحك ظهرا وبطنا وقد (علمت أنها تقتل)

This narration explicitly confirms that only one woman from Banu Qurayza was executed, contradicting claims of indiscriminate killing. According to Ibn Hisham's biography of the Prophet, this woman had killed a Muslim by dropping a millstone on him during the siege. Her execution was thus for a specific act of combat participation rather than for her tribal affiliation or gender. This further supports the conclusion that punishment was based on individual culpability rather than collective punishment.

4.6.6 Sa'd ibn Mu'adh's Status

Anas ibn Malik reports in Jami al-Tirmidhi:

"When Sa'd ibn Mu'adh's bier was being carried, the hypocrites remarked on how light his bier was, and that was because of his judgment concerning Banu Qurayza. The Prophet heard of this and said: 'The angels were carrying him.'"

روى الترمذي في جامعه عن أنس بن مالك – رضي الله عنه- قال: لما حملت جنازة سعد بن معاذ قال المنافقون: ما أخف جنازته، وذلك لحكمه في بني قريظة، فبلغ ذلك النبي ﷺ فقال: «إن الملائكة كانت تحمله»

This hadith indicates divine approval of Sa'd's judgment. The reference to angels carrying his bier symbolizes his righteousness and suggests that his ruling against Banu Qurayza, though severe by modern standards, was considered just within its historical and legal context. This spiritual affirmation reinforces the legitimacy of the judgment within the Islamic worldview.

4.6.7 Analysis of Hadith Sources

These narrations, classified as either sahih (authentic) or hasan (good) by hadith scholars, collectively provide a coherent narrative of the Banu Qurayza incident that aligns with broader historical accounts. Several key conclusions can be drawn:

The punishment of Banu Qurayza was a response to their betrayal during the Battle of the Trench, an existential threat to Medina.

The Prophet Muhammad did not personally determine their punishment but deferred to an arbitrator chosen by Banu Qurayza themselves.

The judgment distinguished between combatants and non-combatants, with only fighting-age men being executed.

The criterion for determining combat eligibility was physical maturity, consistent with legal standards of the time.

Women were generally spared, with only one exception for direct participation in combat.

These primary sources provide crucial context that challenges simplistic characterizations of the incident as religious persecution or indiscriminate violence. Instead, they reveal a complex legal proceeding conducted according to established norms and with procedural protections uncommon in pre-modern warfare.

As we transition to analyzing the legal basis for the judgment in Section 5, these hadith sources provide the factual foundation upon which legal analysis can be constructed.

4.7 Qur'anic References Related to the Banu Qurayza Incident

In Islamic scholarship, the Qur'an always takes precedence as the primary source of guidance, followed by the authentic hadith. However, in discussing the Banu Qurayza incident, we have presented the hadith material first for a specific methodological reason: while the hadith literature explicitly names Banu Qurayza and provides detailed narratives of the events, the Qur'anic treatment is more allusive and contextual, requiring interpretive framework to connect it to this specific historical incident.

The Qur'an, as eternal divine guidance, often addresses events through broader ethical principles rather than detailed historical narratives. Classical exegetes (mufassirūn) have identified certain verses that refer to the Banu Qurayza incident without naming the tribe specifically. Understanding these Qur'anic references in light of the explicit hadith accounts provides a more complete theological and historical framework for interpreting these events.

This section examines three categories of Qur'anic material: verses that contextually reference the Banu Qurayza incident (though not by name), verses that classical commentators have specifically associated with the incident in their tafsir (exegesis), and broader Qur'anic principles of justice that informed the Islamic understanding of this event.

4.7.1 Surah Al-Ahzab (33:26-27): Direct Reference to Banu Qurayza

The most explicit Qur'anic reference to the Banu Qurayza incident appears in Surah Al-Ahzab (The Confederates):

"And He brought down those who supported them among the People of the Book from their fortresses and cast terror into their hearts. A group you killed, and you took a group captive. And He caused you to inherit their lands, their homes, and their properties, and a land which you have not trodden. And Allah is over all things competent."

وَأَنزَلَ الَّذِينَ ظَاهَرُوهُم مِّنْ أَهْلِ الْكِتَابِ مِن صَيَاصِيهِمْ وَقَذَفَ فِي قُلُوبِهِمُ الرُّعْبَ فَرِيقًا تَقْتُلُونَ وَتَأْسِرُونَ فَرِيقًا. وَأَوْرَثَكُمْ أَرْضَهُمْ وَدِيَارَهُمْ وَأَمْوَالَهُمْ وَأَرْضًا لَّمْ تَطَؤُوهَا وَكَانَ اللَّهُ عَلَىٰ كُلِّ شَيْءٍ قَدِيرًا

This passage provides several significant insights. First, it explicitly identifies that those punished were "among the People of the Book" who had "supported" the enemy confederates during the siege of Medina. Second, it uses the phrase "a group you killed" (farīqan taqtulūna) rather than describing wholesale execution, potentially supporting the revisionist interpretation that only the principal conspirators faced execution. Third, it places the event within a broader theological framework of divine judgment for covenant violation rather than presenting it as merely a human decision.

4.7.2 Surah Al-Anfal (8:55-58): The Principle of Covenant Breaking

Another relevant passage appears in Surah Al-Anfal (The Spoils of War):

"Indeed, the worst of living creatures in the sight of Allah are those who have disbelieved, and they will not [ever] believe - The ones with whom you made a treaty but then they break their pledge every time, and they do not fear Allah. So if you, [O Muhammad], gain dominance over them in war, disperse by [making an example of] them those who are behind them, that perhaps they will be reminded. If you fear treachery from any people, throw back [their covenant] to them on equal terms. Indeed, Allah does not like traitors."

إِنَّ شَرَّ الدَّوَابِّ عِندَ اللَّهِ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا فَهُمْ لَا يُؤْمِنُونَ. الَّذِينَ عَاهَدتَّ مِنْهُمْ ثُمَّ يَنقُضُونَ عَهْدَهُمْ فِي كُلِّ مَرَّةٍ وَهُمْ لَا يَتَّقُونَ. فَإِمَّا تَثْقَفَنَّهُمْ فِي الْحَرْبِ فَشَرِّدْ بِهِم مَّنْ خَلْفَهُمْ لَعَلَّهُمْ يَذَّكَّرُونَ. وَإِمَّا تَخَافَنَّ مِن قَوْمٍ خِيَانَةً فَانبِذْ إِلَيْهِمْ عَلَىٰ سَوَاءٍ إِنَّ اللَّهَ لَا يُحِبُّ الْخَائِنِينَ

While not specifically mentioning Banu Qurayza, this passage establishes the Islamic principle for dealing with treaty violations and treachery. It provides the theological foundation for responding to breaches of covenant, particularly when such breaches occur during wartime. The instruction to "throw back [their covenant] to them on equal terms" establishes that when a treaty is violated, the injured party is released from its obligations and may respond proportionately.

4.7.3 Surah Al-Hashr (59:2-4): The Exile of Banu Nadir as Precedent

Surah Al-Hashr (The Exile) refers to the earlier exile of Banu Nadir, providing context for understanding how the Jewish tribes' serial violations of treaties were addressed:

"It is He who expelled the ones who disbelieved among the People of the Book from their homes at the first gathering. You did not think they would leave, and they thought that their fortresses would protect them from Allah; but Allah came upon them from where they had not expected, and He cast terror into their hearts [so] they destroyed their houses by their own hands and the hands of the believers. So take warning, O people of vision."

هُوَ الَّذِي أَخْرَجَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا مِنْ أَهْلِ الْكِتَابِ مِن دِيَارِهِمْ لِأَوَّلِ الْحَشْرِ مَا ظَنَنتُمْ أَن يَخْرُجُوا وَظَنُّوا أَنَّهُم مَّانِعَتُهُمْ حُصُونُهُم مِّنَ اللَّهِ فَأَتَاهُمُ اللَّهُ مِنْ حَيْثُ لَمْ يَحْتَسِبُوا وَقَذَفَ فِي قُلُوبِهِمُ الرُّعْبَ يُخْرِبُونَ بُيُوتَهُم بِأَيْدِيهِمْ وَأَيْدِي الْمُؤْمِنِينَ فَاعْتَبِرُوا يَا أُولِي الْأَبْصَارِ

This passage demonstrates that exile was the preferred punishment for earlier treaty violations, establishing an important precedent. When compared with the treatment of Banu Qurayza, it suggests that the more severe punishment for the latter resulted from the escalating seriousness of their betrayal—occurring during an existential military threat to the entire community—rather than from religious prejudice.

4.7.4 Qur'anic Principles of Justice and Proportionality

Beyond specific references to these incidents, the Qur'an establishes broader principles of justice that provide the ethical framework for understanding the Banu Qurayza judgment:

Surah Al-Ma'idah (5:8) states: "O you who have believed, be persistently standing firm for Allah, witnesses in justice, and do not let the hatred of a people prevent you from being just. Be just; that is nearer to righteousness."

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا كُونُوا قَوَّامِينَ لِلَّهِ شُهَدَاءَ بِالْقِسْطِ وَلَا يَجْرِمَنَّكُمْ شَنَآنُ قَوْمٍ عَلَىٰ أَلَّا تَعْدِلُوا اعْدِلُوا هُوَ أَقْرَبُ لِلتَّقْوَىٰ

Surah An-Nisa (4:58) commands: "Indeed, Allah orders you to render trusts to whom they are due and when you judge between people to judge with justice. Excellent is that which Allah instructs you."

إِنَّ اللَّهَ يَأْمُرُكُمْ أَن تُؤَدُّوا الْأَمَانَاتِ إِلَىٰ أَهْلِهَا وَإِذَا حَكَمْتُم بَيْنَ النَّاسِ أَن تَحْكُمُوا بِالْعَدْلِ إِنَّ اللَّهَ نِعِمَّا يَعِظُكُم بِهِ

These verses establish that justice must be administered without prejudice, even toward enemies, and that fair judgment is a divine commandment. This theological context suggests that the judgment against Banu Qurayza would have been constrained by these principles of justice and fairness, with punishment proportional to the crime committed rather than exceeding it.

4.7.5 Synthesis of Qur'anic Perspective

The Qur'anic references to the Banu Qurayza incident and related events provide a theological framework that emphasizes:

The seriousness of covenant violation, particularly during times of war

The divine sanction for addressing treachery that threatens the community

The principle of proportionality in punishment

The importance of justice even when dealing with enemies

The distinction between combatants ("a group you killed") and non-combatants ("a group you took captive")

When read holistically, these Qur'anic passages suggest that the treatment of Banu Qurayza was not an arbitrary or excessive punishment but a measured response to a serious breach of covenant during wartime, carried out in accordance with legal principles recognized by all parties involved.

The Qur'anic perspective thus reinforces the historical and legal analyses presented in previous sections while adding theological depth to our understanding of how these events were interpreted within the Islamic tradition. This divine sanction for addressing treason does not, however, negate the procedural fairness evident in the Prophet's approach, particularly his delegation of judgment to an arbitrator chosen by Banu Qurayza themselves.

5. The Legal Case Against Banu Qurayza

The trial and sentencing of Banu Qurayza following the Battle of the Trench represents the culmination of the political and legal developments in early Medinan society. To properly understand this event, one must examine who passed judgment, the legal basis for the ruling, and whether the sentence aligned with existing legal frameworks.

5.1 Who Passed Judgment?

A critical fact often overlooked in discussions of the Banu Qurayza incident is that the Prophet Muhammad did not personally determine their punishment. According to Ibn Ishaq (1998, p. 402), "When Banu Qurayza surrendered, they requested Sa'd ibn Mu'adh, an ally of theirs, to decide their fate." This detail is significant for several reasons.

First, Sa'd ibn Mu'adh was a respected leader of the Aws tribe and had maintained a close relationship with Banu Qurayza before the rise of Islam. The tribe's specific request for him as arbitrator demonstrates their expectation of favorable treatment based on their prior alliance. As Watt (1956, p. 151) notes, this follows "tribal legal customs of appointing an arbitrator to resolve conflicts" and was a common practice in pre-Islamic Arabia.

Second, the Prophet's deferral to Sa'd's judgment illustrates that this was a legal proceeding rather than an arbitrary act of vengeance. By accepting the tribe's chosen arbitrator, the Prophet demonstrated commitment to established legal processes rather than imposing direct retribution.

Third, Sa'd's role as judge creates a critical distinction between Islamic law and the specific ruling applied in this case. As will be discussed, Sa'd explicitly based his judgment on Jewish law rather than Islamic principles, creating a legal separation between this specific verdict and Islamic jurisprudence more broadly.

5.2 The Legal Basis: Jewish Law and Deuteronomy

Upon being appointed judge, Sa'd ruled according to Jewish law, specifically invoking the principles found in Deuteronomy 20:10-14, which states:

"When you march to attack a city, offer peace. If they refuse and fight, put to the sword all the men. The women and children may be taken as captives."

Ibn Hisham (1955, p. 356) records that "Sa'd ruled that all the men should be executed, and the women and children should be taken captive, in accordance with the Book of God." This reference to "the Book of God" in context refers to the Torah rather than the Qur'an.

The legal implications of this ruling are profound. Sa'd's explicit reference to Jewish law means that Banu Qurayza were judged according to their own religious legal tradition rather than being subjected to foreign standards. Jonathan Brown (2017, p. 217) emphasizes that this "was a legal judgment under their own tradition, not an arbitrary massacre."

Furthermore, the application of Deuteronomy's principles aligns with the tribe's legal expectations. As members of a Jewish community who recognized the Torah as authoritative, they would have understood that treason during wartime carried severe penalties under their own legal tradition.

5.3 The Definition of Treason in Pre-Modern Legal Traditions

Banu Qurayza's actions during the Battle of the Trench constituted what would be recognized across legal traditions as high treason—the betrayal of one's political community during wartime. Their secret negotiations with Quraysh, if successful, would have resulted in the destruction of Medina and the death of countless inhabitants, including women and children.

Under both Jewish and pre-Islamic Arabian law, treason was considered the gravest political crime, typically warranting capital punishment. The Qur'an acknowledges this legal principle in Surah Al-Anfal (8:58): "If you learn of treachery from a people, respond in kind, but do not be unjust."

It is essential to understand that the concept of treason in pre-modern societies differed significantly from modern interpretations. In the absence of strong centralized states with professional militaries, the betrayal of one's community during war presented an existential threat that could result in the complete annihilation of one's society. The harsh penalties for treason reflected this reality rather than arbitrary cruelty.

5.4 Addressing Historical Questions About the Numbers

The historical accounts of the Banu Qurayza incident typically suggest that between 600-900 men were executed following Sa'd's judgment. However, several scholars have questioned the accuracy of these figures.

Reuven Firestone (1999, p. 198) notes that 'early Islamic sources vary widely on the number of executions, with some estimates as low as 100-200.' Fred Donner (2010, p. 195) similarly observes that 'Medina's total population at the time could not have supported 900 fighting men' from a single tribe, suggesting that the higher estimates may be exaggerated. Some contemporary scholars go further, suggesting that only the tribal leadership—approximately nine individuals who orchestrated the betrayal—were executed, rather than the general male population. Sah Rabih Situn Nadir and Ismail Mohammed Jalal (2022) identify specific leaders including Huyayy ibn Akhtab, Ghazal ibn Samoal, Wahb ibn Zayd, Zubayr ibn Bata, Nabash ibn Qays, Ka'b ibn Asad, Uqbah ibn Zayd, and others, arguing that primary sources have conflated the punishment of these leaders with the fate of the entire tribe.

This revisionist interpretation finds indirect support in the Quranic account of the incident, which refers to killing 'a group' (farīqan) rather than all men, potentially indicating that punishment was targeted rather than comprehensive. Furthermore, this reading would be more consistent with the Prophet's handling of previous treaty violations by Jewish tribes, where exile rather than execution was the preferred solution even for serious breaches of security

5.5 Scholarly Consensus on the Legal Nature of the Judgment

Academic historians from diverse backgrounds generally agree that the Banu Qurayza incident must be understood as a legal proceeding rather than a religious persecution. Montgomery Watt (1956), Bernard Lewis (1984), Reuven Firestone (1999), and Jonathan Brown (2017) all characterize the judgment as a wartime legal ruling consistent with pre-modern norms.

Bernard Lewis (1984), a prominent historian of Islam, emphasizes that "the decision was based on Jewish law, not Islamic law," while Jonathan Brown (2017, p. 219) concludes that "this was a case of treason, not religious persecution." Even scholars critical of certain aspects of early Islamic history acknowledge that the punishment of Banu Qurayza followed established legal precedents of the time.

This scholarly consensus refutes several common misconceptions about the incident. First, it challenges claims that the punishment reflected religious persecution, as the judgment was based on political treason rather than religious identity. Second, it demonstrates that the ruling was not arbitrary or vengeful but followed established legal procedures. Third, it shows that the sentencing was proportional to the crime according to pre-modern legal standards, not an excessive or unprecedented punishment.

6. Comparative Analysis of Wartime Justice in Other Civilizations

To properly contextualize the Banu Qurayza incident, it is essential to compare it with how other pre-modern and even modern civilizations have addressed wartime treason. Such comparative analysis reveals that similar or even harsher legal precedents existed across Jewish, Roman, Christian, and modern legal traditions.

6.1 Jewish Law and Deuteronomy

As previously established, Jewish law as codified in Deuteronomy 20:10-14 prescribed execution for enemy combatants who refused terms of peace and fought against Jewish forces. This practice was not limited to theoretical religious texts but was applied throughout Jewish history.

Reuven Firestone (1999, p. 202) observes that "Jewish law prescribed execution for enemy combatants, even after surrender" and that "women and children were taken as captives, similar to Banu Qurayza's case." Unlike later Islamic warfare, which developed alternatives such as ransom or exile, Deuteronomic law did not explicitly offer such alternatives.

When comparing these legal standards with the Banu Qurayza case, it becomes evident that Sa'd's ruling aligned perfectly with established Jewish legal tradition. The Qur'an, by contrast, offers more merciful alternatives in Surah Muhammad (47:4): "When you meet the disbelievers in battle, strike them until subdued, then release them either as a favor or for ransom." However, critical scholars have questioned whether Deuteronomic law was applied to the entire tribe or only to its leadership. The principle of proportionality in punishment, which appears in both Jewish and Islamic traditions, suggests that punishment should correspond to the degree of involvement in the crime. From this perspective, mass execution would represent a departure from the principle of individual responsibility, while targeted punishment of the conspiracy's architects would better align with both religious traditions' emphasis on justice.

6.2 Roman Law and the Crime of Maiestas

The Roman Empire established some of history's most developed legal codes, including specific provisions for treason (maiestas). Under Roman law, treason was considered the most severe offense, often punished by crucifixion, exile with property confiscation, or public humiliation before death.

The Lex Julia de Maiestate (48 BCE) codified that any city-state or province that betrayed Rome faced total destruction, with all combat-age men executed and survivors sold into slavery. As Donald Kagan (2003, p. 287) notes, Roman military law "did not distinguish between traitors and conquered populations" and frequently resulted in "entire cities being wiped out for political treason."

Compared to Roman legal practice, the treatment of Banu Qurayza was relatively restrained. The tribe received a formal trial with a chosen arbitrator, whereas Roman traitors were often executed without trial. Furthermore, Islamic law ensured women and children were protected, while Roman practice frequently enslaved entire populations regardless of age or gender.

6.3 Medieval Christian Europe

Medieval Christian societies treated treason as a crime against both temporal and divine authority, often resulting in particularly severe punishments. The case of William Wallace in 1305 exemplifies this approach—accused of treason against England, he was "hanged, drawn, and quartered—his body mutilated and publicly displayed" (Gillingham, 2002, p. 118).

The Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) provides another instructive comparison. The Catholic Church executed thousands accused of heresy and treason, often using torture before execution. As Henry Kamen (1997, p. 145) documents, "Muslims and Jews accused of treason were burned at the stake" with "no due process observed—judgments were made in secrecy."

These examples from medieval European jurisprudence underscore the relative restraint shown in the Banu Qurayza case. Islamic justice involved an open trial with a judge chosen by the accused, prohibited torture (unlike medieval Christian courts), and limited punishment to those directly involved in the conspiracy rather than entire communities.

6.4 Modern Wartime Justice

Even in the modern era, wartime treason has typically resulted in severe punishment. Following World War II (1939-1945), many governments executed individuals accused of collaboration with enemy forces.

In France, "over 10,000 French citizens were executed for collaborating with the Nazis" between 1944-1945 (Keegan, 2000, p. 344). These executions often occurred through firing squads or summary proceedings, frequently without formal trials. Similarly, the United States executed German saboteurs in 1942 through military tribunals, "even though they had not engaged in active warfare" (Taylor, 1992, p. 276).

These modern examples demonstrate that even societies generally recognized for their commitment to due process have imposed capital punishment for treason during times of war. The trial of Banu Qurayza, when viewed in this comparative context, appears consistent with legal norms that have persisted across cultures and historical periods.

7. The Qur'an as the Standard of Justice

When analyzing Islamic governance and legal principles, it is essential to recognize the Qur'an's paramount role as the standard of justice that guides all jurisprudence and political conduct. The Qur'anic foundation for justice provides a consistent framework against which all legal decisions, including wartime judgments, must be measured.

The Qur'an repeatedly emphasizes justice as a foundational principle, stating in Surah An-Nisa (4:58): "Indeed, Allah commands you to judge with justice." This imperative is further strengthened in Surah Al-Ma'idah (5:8): "Let not hatred of a people lead you to injustice." These verses establish that Islamic governance prohibits unjust punishment and requires fairness even toward enemies or those with whom Muslims have disputes.

The Qur'anic emphasis on justice extends to governance and the administration of law. The Prophet Muhammad's broader governance model was characterized by mercy and restraint, as exemplified by his general amnesty to the people of Mecca following its conquest in 630 CE. Despite years of persecution at their hands, the Prophet forgave his former oppressors, setting a precedent for clemency and magnanimity that stands in stark contrast to typical patterns of retribution in pre-modern societies.

Significantly, the Qur'an provides a self-correcting mechanism against tyranny and governmental overreach. Unlike many political systems that enable unchecked power, Islamic governance incorporates inherent limitations on authority through its insistence that rulers remain subject to divine law. As noted by Wael Hallaq (2009, p. 151), throughout Islamic history, scholars like Imam Abu Hanifa refused to support Abbasid rulers when they oppressed their people, demonstrating that "Islam does not teach blind obedience to authority."

This self-correcting mechanism manifests in the obligation of Muslims to oppose unjust rulings and stand for righteousness, even when doing so challenges established authority. The Prophet Muhammad affirmed this principle, stating: "The best of leaders is the one who rules with justice, and the worst is the tyrant" (Hadith, Sahih Muslim, 1855). This creates a framework in which Muslims are required to resist tyranny and oppression, providing a built-in safeguard against the abuse of power.

8. Conclusion: Islam as the Ultimate Model of Justice

The thorough examination of the Banu Qurayza incident in its historical, legal, and comparative context reveals several key conclusions that challenge prevailing misconceptions about this event and Islamic governance more broadly.

First, the case against Banu Qurayza was fundamentally a legal trial for treason, not religious persecution. The tribe's violation of the Constitution of Medina during the Battle of the Trench constituted a grave act of wartime betrayal that endangered the entire Medinan community. Their punishment was a response to this specific political crime rather than to their religious identity. While traditional accounts suggest larger numbers of executions, revisionist scholarship offers an alternative reading that limits punishment to tribal leaders directly responsible for the conspiracy, which would align more closely with the Prophet's documented preference for clemency in other situations. This interpretation is supported by critical analysis of the source materials, consideration of Medina's demographic realities, and examination of the Quranic text itself, which describes the killing of 'a group' rather than wholesale execution. If accurate, this reading would further reinforce that the punishment was precisely targeted at those responsible for the treasonous conspiracy rather than representing collective punishment.

Second, the ruling was based on Jewish legal principles as articulated in Deuteronomy, not on Islamic law. Sa'd ibn Mu'adh, chosen by Banu Qurayza themselves as their arbitrator, explicitly referenced Jewish legal tradition in rendering his judgment. This demonstrates that the tribe was judged according to standards they themselves recognized as legitimate.

Third, comparative analysis of wartime justice across civilizations reveals that the punishment of Banu Qurayza was consistent with global legal norms from ancient to modern times. Jewish, Roman, Christian, and even modern legal systems have imposed similar or harsher penalties for treason during wartime, often with less procedural protection than was afforded to Banu Qurayza.

Fourth, Islamic governance incorporates a self-correcting system that prevents manipulation and despotism. The Qur'an's emphasis on justice, fairness, and proportionality establishes boundaries that rulers cannot transgress without losing legitimacy. Muslims are obligated to resist unjust leadership, ensuring that Islam does not permit oppression even when committed by those who claim religious authority.

The misrepresentation of the Banu Qurayza case in contemporary discourse often stems from historical ignorance or ideological bias. When properly contextualized, this incident does not demonstrate Islamic intolerance or brutality but rather illustrates a legal system operating according to established norms while maintaining procedural protections uncommon in pre-modern jurisprudence.

As the Qur'an states in Surah An-Nisa (4:58): "Indeed, Allah commands you to judge with justice." This divine imperative remains the foundational principle of Islamic governance, establishing a standard that continues to guide legal and political thought. Islam, when properly understood and applied, represents an ethical and balanced legal system that prioritizes justice over arbitrary power and mercy over retribution.

Bibliography

Armstrong, K. (1991). Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet. Harper San Francisco.

Brown, J. (2017). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oxford University Press.

Donner, F. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Harvard University Press.

Firestone, R. (1999). Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. Oxford University Press.

Gillingham, J. (2002). The Wars of the Roses: Peace and Conflict in Fifteenth-Century England. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Hallaq, W. (2009). Shari'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations. Cambridge University Press.

Hawting, G. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. Routledge.

Ibn Hisham. (1955). Al-Sirah al-Nabawiyyah. (M. al-Saqqa, Trans.). Cairo: Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi.

Ibn Ishaq. (1998). The Life of Muhammad. (A. Guillaume, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Kagan, D. (2003). The Peloponnesian War. Viking.

Kamen, H. (1997). The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. Yale University Press.

Keegan, J. (2000). The Second World War. Penguin Books.

Lewis, B. (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton University Press.

Taylor, T. (1992). The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials. Knopf.

Watt, W. M. (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press.

Nadir, S. R. S., & Jalal, I. M. (2022). The new reading of the invasion of Banu Qurayza, a critical investigation study. Islamic Sciences Journal, 13(7), 119-148. https://doi.org/10.25130/jis.22.13.7.2.6