#63: Terrain, Not Slogans – How Strategy, Friction, And Architecture Decide Which Systems Live And Which Collapse

From personal habits to platforms and revolutions: mapping Earth, building scaffolds, and using tempo and guardrails so new patterns can actually survive contact with the real world.

By the time you finished the last essay, one thing should already be hard to unsee: habits and systems do not fall because you “try harder”. They fall when the road under them changes.

You can make almost any path unbearable if you add enough gravel.

You can make almost any path acceptable if you quietly level and light it.

So the real question now is not “how do I motivate people”

but something colder:

If friction decides which path survives, who decides where the roughness goes first, and what is the first intelligent move in that design?

You can ask this about almost anything:

Why do old habits die hard, even when people say they are done with them.

Why does tapping a card feel easier than handing over cash.

Why do activists burn bright and then go numb.

Why do most fitness programs work for a season and then evaporate the moment life tilts.

The answers people give on the surface are nearly always psychological. Motivation. Will. Belief. Discipline.

Underneath, something else is deciding.

September, 629 CE. A valley called Mu’ta, in what is now Jordan.

Khalid ibn al-Walid stands in dust with roughly three thousand men, facing a Byzantine and Ghassanid force reported at tens of thousands, possibly as high as one hundred thousand. The exact number is debated by historians, but everyone agrees on the core fact: the Muslims are outnumbered badly. Three commanders have already died holding the line. Khalid inherits command in the middle of a battle that is already going wrong. (For the campaign background, see Donner, 1981; Agha Ibrahim Akram, The Sword of Allah, 1970.)

If this were a movie, you know what would happen next. The script everyone knows is simple: shout about honor, charge the center, die beautifully.

That is not what happens.

What Khalid does instead looks cowardly to many of his contemporaries. He pulls back. Not in panic. Not as a rout. He pulls back methodically and at night. He shuffles units so that when the Byzantines wake, they see familiar banners in slightly different positions, unsure whether the Muslims are leaving or regrouping. He withdraws in fighting formation, bleeding the Byzantine advance with ambushes and harassment at every mile, making pursuit feel less like a victory march and more like walking into a trap that might or might not exist.

Within days, he extracts the entire force. Losses are painful, but the army survives. When they return to Medina, some people throw dust at them and call them cowards. “You fled!” someone shouts. In the sīrah and early histories this tension is recorded plainly: some saw Mu’ta as failure; others as necessary preservation. (Donner, 1981; Ṭabarī, Tārīkh al-Rusul wa’l-Mulūk.)

Most retellings stop at “tactical brilliance” or “divine favor”.

But if you look at it as a systems architect, something sharper appears.

Khalid reads three gradients:

Stay and fight: slow death by attrition. Courage cannot multiply bodies indefinitely.

Advance into the center: fast death by encirclement. The Byzantines can absorb the charge and close.

Retreat: survivable, but only if he can make each Byzantine step forward feel more dangerous than stopping.

He doesn’t “decide to be brave” or “decide to be loyal to the troops”. He reads the field as a set of channels, chooses the only one that does not end in total collapse, then spends all his tactical intelligence making that path smoother for his side and rougher for the enemy.

This is not a story about whether retreat is honorable.

This is a story about someone who understood, deep in his bones, that outcomes follow gradients, and gradients can be designed.

Most people who talk about changing systems never get past that second sentence. They talk about vision. They talk about values. They talk about what the world should look like, what people should care about, how we all should live.

And often they are right.

But they rarely draw the map that shows where the energy will actually flow day to day once the speech is over and everyone goes home. They never ask which route is easy, which is perilous, who controls the bridges, who controls the gates.

That is where this essay begins.

1. Terrain, not slogans

Most people who talk about changing systems never reach that second sentence. They talk about vision, values, what the world should look like, what people should care about. Often they are right on the moral content.

They just never draw the map.

They never ask: which route is easy, which is perilous, who controls the bridges, who controls the gates. They speak in the language of ideals and identity, then send those ideals to walk across a landscape they have not measured.

Sun Tzu, writing about two thousand years before Khalid, breaks his thinking into five constant factors: the Way, Heaven, Earth, the Commander, and Method. He is not being mystical; he is naming layers of structure that decide who survives contact with reality. (Sun Tzu, trans. Sawyer, 1994.)

The Way is alignment: what this system is for and who it truly serves.

Heaven is larger cycles and conditions you do not directly command: timing, climate, seasons, the “weather” of politics and economics.

Earth is concrete terrain: distances, chokepoints, open vs constricted ground, places of likely life and death.

The Commander is the decision style under stress: wisdom, sincerity, courage, discipline.

Method is organisation and logistics: supply lines, routines, the scaffolding that keeps form under strain.

Most modern “system change” lives entirely in the Way. Movements talk about values, liberation, regeneration, “the future we deserve”. Much of that is true. But the feet of their followers still walk the same roads.

Heaven is ignored; timing and cycles are treated as if they will politely adjust. Earth is barely mapped: the actual defaults, interfaces, incentive structures and schedules that decide where energy flows day to day. Commanders are not trained; people who must make decisions in the field are left exposed and improvising. Method is an afterthought; the dull weekly work of logistics and repetition is treated as beneath the vision.

A strategist begins with all five, but if you only fix one, you fix Earth.

Because in modern language, Earth is not a metaphor. It is the configuration of your digital interfaces, the billing cycles, the notification patterns, the physical layout of your city, the form fields and ID requirements that make one behaviour smooth and another exhausting. One can see this in everything from default enrollment in pension plans to opt-out organ donation systems, where changing the default flips participation rates with no moral persuasion at all (Johnson & Goldstein, 2003; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

John Boyd, working from fighter combat a couple of millennia later, restated the same insight in time instead of geography. Whoever cycles faster through Observe–Orient–Decide–Act, or slows the opponent’s cycle with friction and confusion, gains the upper hand (Boyd, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, compiled lectures). Thomas Schelling, thinking about strategy in nuclear standoffs, discovered that people naturally coordinate on “focal points” that feel obvious without discussion, like “meet at noon at Grand Central” in New York (Schelling, 1960).

Three very different minds, three different centuries, pushing toward one conclusion:

If you intend change that endures, your first duty is not to announce a better story. It is to map the terrain your story must travel across.

Where the channels of least resistance run. Where small obstacles redirect entire flows. Where empty basins sit, waiting for any trickle to grow into a river.

Until that map is drawn, you are not doing strategy.

Red + blue are how you see and decide (Sun Tzu + Boyd). Green is where you actually move gradients in the real world (Khalid’s actuator layer).

2. Supply lines and scaffolds

Armies rarely die for lack of courage at the front. They die because food, water, and replacements stop arriving. Sun Tzu says it without romance: prolonged campaigns exhaust the state; you dull your own sword by keeping it in the field too long without resupply (Sun Tzu, trans. Sawyer, 1994).

Permanent change is a long war. Its supply lines are time, attention, and reinforcement.

At the individual level, this looks like something unglamorous: a scaffold. In construction, a scaffold is a temporary structure that lets a new form hold together while it cures. In behaviour, the analogue is painfully simple: regular cues, protected slots of time, and over-support in the fragile phase, so the new pattern does not collapse under the weight of old routines.

Behavioural work is very clear on this point. Changes that are anchored to recurring cues, pre-decided “if–then” plans, and social structures are far more likely to stick than vague resolutions (Gollwitzer, 1999; Fogg, 2009). A weekly support group, a fixed check-in call, a shared practice time: these are not “nice extras”. They are supply lines.

Boyd’s loop gives the logic. In a chaotic field, you must stabilise your own OODA loop while making your opponent’s loose and slow. For habits and systems, “the opponent” is yesterday’s groove.

A scaffold does two jobs at once:

It shortens the distance between cue and desired action.

It lengthens and complicates the distance to relapse.

A weekly meeting for recovering addicts is not magic. It is a pre-drawn circle on the calendar that makes “I feel the slip coming” quickly convertible into “I am in a room where this slip is not normal.” Structured programs that front-load supervision, peer accountability, and practical support function as supply convoys for a different life. Cognitive-behavioural approaches explicitly combine this kind of environmental and routine design with thought work for that reason (Beck, 2011).

Treat movements and institutions with the same cold eye.

A cause that only asks for episodic sacrifice, that lives on marches and viral peaks, will starve. A cause that quietly fixes a ten-minute action window every Friday at the same time, and never misses it for a decade, is laying tracks.

Yarmouk, 636 CE.

The Byzantine Empire fields perhaps eighty to one hundred and twenty thousand soldiers; Muslim sources and modern historians differ on precision but agree this is one of the largest forces of its time (Kaegi, 1992). They occupy high ground, with ravines guarding their flanks. Khalid has something like twenty-five to forty thousand men. Numbers are fuzzy; the asymmetry is not. If this becomes a grinding contest of attrition, he loses.

Most commanders, feeling that pressure, would put everyone on the front line. If you lack numbers, at least make the line look solid.

Khalid does the opposite. He divides his forces into a center and a mobile guard. The center’s job is to hold and absorb pressure. The mobile guard, his best cavalry, sits in a protected slot behind the line. They are not committed to any patch of ground. Their command is simple: move fast, hit weak points, rescue collapsing segments, and do not wait for permission.

This is logistics as freedom-to-act.

Because the mobile guard has a clear role, clear resourcing, and pre-authorised freedom within bounds, they can cycle through their own OODA loops far faster than a unit that must always ask “may we disengage?” or “may we counterattack?”. Khalid has built a scaffold inside the army: a structure that makes certain actions cheap and quick for chosen units, while the rest holds shape (Agha Ibrahim Akram, 1970; Kaegi, 1992).

Most organizations never build this. They either lock everyone into rigid positions, requiring permission for every deviation, or they shout “be empowered!” without removing any of the barriers that make empowered action expensive and dangerous for individuals.

A permanent change system that neglects scaffolds is asking its soldiers to fight without supply. It might win a skirmish. It will not last a campaign.

3. Guardrails and the cost of retreat

In the first essay we already saw one basic pattern: established systems protect their habits by making exits expensive and entry easy. That is not ideology; it is simply what survives when power understands terrain.

If you want change to hold, you must do the same in reverse, and you must do it without lying about what you are doing.

Schelling built much of his strategy work on one idea: commitment. The side that can credibly limit its own options can shape the expectations and behaviour of others, whether through unburnable bridges or inviolable promises (Schelling, 1960). In systems design, commitments embodied in structure function as guardrails.

A cooperative that locks “one member, one vote” and strict income caps into its bylaws makes a slide into standard shareholder capitalism legally costly. A city that rips out car lanes to install protected tram and bike corridors signals that reversing this will require real money and political cost. A country that embeds certain rights and obligations into a constitution raises the hill in front of any attempt to rollback.

Families do the same at small scale when they elevate certain decisions beyond daily bargaining. “Devices do not cross this threshold after 9 pm.” “Friday evenings are reserved for this shared act.” Once these are not re-litigated every week, they begin to operate like guardrails.

Guardrails are asymmetry turned into architecture.

Breaking the new pattern should feel heavier than continuing it. Not infinitely heavier. Just heavy enough that on an ordinary tired day, the path of least resistance runs through the new pattern, not around it.

Back to Mu’ta.

Khalid has already read the gradients and chosen retreat as the only survivable channel. But the execution reveals the guardrail logic.

For his own soldiers, retreat cannot feel like rout. If it feels like collapse, cohesion will shatter and the Byzantines will cut them down in the open. So Khalid designs retreat as tactical repositioning: formation maintained, night movements, familiar banners seen in the morning, constant small counter-strikes. The gradient is shaped so that staying in formation feels safer than panicked flight.

For the Byzantines, pursuit must feel dangerous. If chasing feels cheap and safe, they will follow until the smaller force is destroyed. So he turns every mile into a maybe-trap. Scouts are hit. Harassment continues. The enemy never knows whether they are pursuing a broken army or walking into a planned ambush. The gradient flips: stopping feels prudent; charging forward feels like volunteering for the unknown.

He has not changed the character of either army. He has changed the costs.

Most new systems never bother. They rely on everyone maintaining peak commitment indefinitely. Guardrails are replaced with pep talks. When mood, leadership, or funding dips, the pattern collapses and people drift back to the old riverbed.

Khalid would not call that a failure of will. He would call it a failure of design.

4. Focal points, rituals, and shared time

Sun Tzu talks about flags, drums, and signals. In the fog of battle they let dispersed men move as a single body. Modern strategy uses a drier term for similar phenomena: focal points. Schelling showed that when people must coordinate without talking, they often gravitate toward solutions that feel natural in context, even if nothing was agreed explicitly beforehand (Schelling, 1960).

Permanent change depends on such anchors in both space and time.

You cannot keep telling millions of people “do your part whenever you can” and expect a stable pattern to emerge. The space of possibilities is too large and attention too fragmented. Coordination fails quietly.

If you want a practice to survive you, you give it:

A fixed time that is common knowledge.

A simple act that fits that time.

A symbol that marks the act as shared.

Friday congregational prayer did this at civilizational scale: one day, one directional band in time, one orientation, one basic script. No app, no email list. Just a repeated focal point where otherwise scattered lives braid into one act.

Activism and regeneration projects can pick up the same logic without borrowing the theology. Pick a day and a narrow time band, attach one coordinated act to it every week, and refuse to move that slot. The details of the act can evolve; the slot becomes sacred in the structural sense. Over years it turns into a Schelling point: “if you care about this, this is when you move”.

Ritual here is not decoration. It is time-architecture.

Khalid did not invent the prayer schedule, but he used it. One quiet elegance of the Islamic timetable is that the anchor points are keyed to the sun, not to mechanical clocks: dawn, solar noon, mid-afternoon, sunset, night. That means soldiers scattered across different latitudes and landscapes can coordinate to a shared sky, rather than a shared device.

In campaign terms, this creates coordination infrastructure that does not depend on fragile tools. “At Dhuhr on the third day” is legible to every unit with a horizon. No centralized broadcaster needed.

On the field at Yarmouk, visual focal points matter too: dust plumes, banners, the density of the center. But more important than the signals is what they signal. Khalid treats the infantry center as a moral and structural anchor. Everybody understands: if that collapses, the whole army dissolves. That understanding is design, not accident.

Modern movements rarely bother to build these anchors. They state broad commitments and values; they neglect rally points. When things get rough, followers do not know where or when to converge. Coordination becomes an endless negotiation on messaging apps.

If the first essay was about friction, this layer insists that you also design focal points. A change without such shared anchors is an army that has forgotten its signals and tries to fight as scattered individuals.

5. Tempo and adversaries

Boyd’s OODA loop was not meant as a productivity hack. It was his attempt to explain why some pilots seemed to “get inside” the enemy’s decision cycle: seeing, interpreting, deciding, and acting in a way that constantly made the other side wrong-footed (Boyd, compiled in A Discourse on Winning and Losing).

To design permanent change you have to admit something uncomfortable: if the existing system is what you are trying to displace, then in this sense it is your adversary. Not necessarily evil in every part. But structurally inclined to resist some transitions and to restore its old flows whenever possible.

Sun Tzu warns against meeting a stronger force on its chosen ground. Boyd just quantifies it: if the other side can Observe–Orient–Decide–Act faster than you, with greater resources and finer instruments, you will be the one constantly reacting.

That describes most activism and “new system” projects today. They are loud and legible. They announce their intentions in advance. They move predictably, with recurring tactics and routes. The incumbent observes them clearly, orients with full institutional memory and legal advice, decides with calm access to budgets and coercive power, and acts with all of that behind each move.

The insurgent is trying to run a faster OODA loop while making it effortless for the incumbent to run its own even faster.

Khalid’s handling of Yarmouk is the opposite.

The Byzantine army is a machine built for set-piece battle: heavy infantry blocks, cavalry, chained Armenian units that must stand ground, layered command from imperial appointee down (Kaegi, 1992). It excels when the situation is stable and orders can propagate along known paths. It struggles when information is partial and the situation keeps twisting before orders can be updated.

Khalid keeps his own information flowing with small, fast cavalry probes and constant reports. He uses prayer times as natural coordination points. He harries Byzantine scouts and throws out feints so that the enemy cannot be sure where the main pressure will land next. Their Observe step is corrupted. Their Orient step must run up and down a slow hierarchy. By the time they Decide and Act, he has already shifted pressure somewhere else.

Crucially, he does not maintain constant speed. He uses arrhythmic pressure: hit one flank hard, pull back, let them start to stabilize and redeploy, then hit another point before that redeployment completes. The result is an opponent that never quite catches its breath, never sees a stable pattern to adapt to.

After days of this, he uses the terrain itself to break their decision cycle. He drives retreating units toward ravines where chained soldiers cannot maneuver. At that point, choices collapse from “hold, pivot, or fall back” to “stand and die, or retreat into fatal ground”. Cohesion dissolves; each man makes a survival decision. The system stops acting as a system.

Translating this back into civil language:

If you design as if no one will push back, you are already writing your failure into the blueprint.

If you design as if your opponent will always be stupid, slow, or honest, you are courting disappointment.

Permanent change systems begin where the incumbent is not looking: neglected corners of law, side-channels of finance that do not rely on interest, overlooked professions, small towns, unglamorous tools. In these pockets you can shorten your own loops, refine scaffolds and guardrails, and build density before you are a visible target.

Once your pattern has internal reinforcement, broader confrontation becomes less suicidal. You are no longer a mood. You are a structure.

6. A small battlefield: your bed, your phone, and 23:30 - An Example …

Take the smallest battlefield you actually control: your bed, your phone, and the half hour after you should already be asleep.

On paper you want rest and clarity. In practice, three or four nights a week you end up face-lit by a rectangle, scrolling through feeds you will not remember.

Read this the way a general would.

Your Way is officially “sleep and health”. The lived Way of the system is closer to “numb and distract”. That kind of gap between stated aim and actual function is exactly what sits behind chronic self-sabotage in individuals and institutions alike (Baumeister & Tierney, 2011).¹

Heaven is tilted against you: it is late, blood sugar low, emotions stirred. Under fatigue and stress people consistently pick the short-term, easier option, even when they know it is worse (Kouchaki & Smith, 2014).²

Earth is engineered to feed the loop: phone on the bedside, plugged in, notifications on, tempting apps on the first screen. A single arm’s reach and thumb movement carries you from “I feel a flicker of unease” into a feed. Behaviour designers have shown over and over that small changes in effort or friction can flip real-world behaviour more than big changes in attitude (Fogg, 2009; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).³ ⁴

The Commander at that hour is not the same mind that writes plans. Night-you is depleted and seeking comfort. Under ego depletion people fall back into habitual responses, even when they sincerely endorse different values (Hagger et al., 2010).⁵

The accidental Method is a routine: collapse into bed, phone in hand, scroll until the brain gives up.

Inside that geography, the nightly OODA loop is boringly stable. You observe a twitch of boredom and the shape of the phone. You orient with a soft story: “just five minutes, I earned this.” You decide to watch one more clip. You act with unlock, scroll, tap. Each act spawns fresh observations as the feed refreshes.

On the other side of the glass, a recommendation system runs its own loop at machine speed, tuned to maximise engagement rather than rest (Zuboff, 2019; Alter, 2017).⁶ ⁷ You are not losing to “weak will”. You are losing to a better-designed system with better logistics.

Khalid’s grammar lets you stop treating this as a character flaw and start treating it as a field problem.

You prepare the field during the day when your Commander is still sane. You list the dependencies: phone in the bedroom, charger at the bedside, unstructured decompression, no witness. You move the charger out. You buy a cheap alarm clock so “I need the phone for my alarm” dies as an excuse. You place a Qur’an, a slim book, or a notebook near the bed. You tie a short shutdown ritual to a fixed anchor, for example after ʿIshā’. Psychologists call these if–then “implementation intentions”, and they reliably increase the odds that intentions turn into action (Gollwitzer, 1999).⁸

You remap the flows so that the path into sleep is smooth and the path into the feed is rough. Shutdown becomes a simple script you perform the same way every night. Access to feeds now carries friction: log-outs, app limits, grayscale screen, apps buried several swipes deep. The same “sludge” tools regulators use to quietly discourage bad choices can be used on yourself: small, well-placed frictions cut usage dramatically (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008; Sunstein, 2019).⁴ ⁹

Then you engineer cascades. You track phone-free nights in ink somewhere visible. You make a quiet rule in the household that phones do not cross a given threshold after a certain hour. Streak-based tracking taps directly into loss aversion; once a streak exists, people will work harder not to break it (Milkman et al., 2021).¹⁰ Better sleep produces clearer mornings, which you consciously link back to the shutdown pattern. Cognitive-behavioural work has long stressed that durable change comes from altering routines and environments alongside thoughts, not thoughts alone (Beck, 2011).¹¹

Over weeks, the gradient reverses. Doomscrolling in bed feels awkward and faintly shameful. The shutdown ritual feels simple and clean. You are no longer relying on motivational spikes. You have moved the road.

A single habit, treated as a campaign, already holds the full stack: Sun Tzu reading the field, Boyd timing the loop, Khalid moving the flows.

If this grammar can bend something as petty as a bedtime, it can bend supply chains, bylaws, and city layouts. The pattern does not care about size. Only about terrain.

So the next step is to stop thinking like a patient or a user, and pick up the tools as an architect.

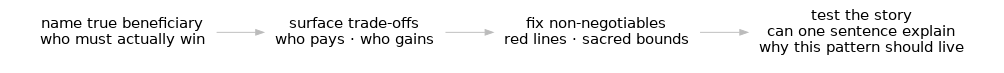

7. A short manual for architects of the real

Sun Tzu’s line still hangs in the air: if you know yourself and know the enemy, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

In this context, “knowing yourself” is knowing the behaviour you want, at what cadence, and at which scales. “Knowing the enemy” is understanding the gradients that keep the opposite pattern alive, and the ways the incumbent system will quietly restore them.

From there the moves are not mystical. They are carpentry.

You choose one pattern that must endure. You clarify its first move.

Not a vision. Not a value statement. A specific action that someone can take this week, next week, the week after. The pattern must have a shape you can point to.

“Every Friday at sunset, we act.”

“Devices leave the bedroom at 9 pm.”

“One member, one vote, locked in the bylaws.”

If you cannot describe the first move in a single sentence, you are not ready to design the system.

You build scaffolds around that move in time and space.

The new pattern is fragile. It needs protection. So you carve non-negotiable slots in the calendar, anchor them to existing rhythms, and remove small barriers between cue and action. In Yarmouk terms, you make sure your mobile guard has a protected lane and pre-authorised freedom to move. In personal terms, you fix a check-in, a room, a budget line that does not need to be re-argued every month.

You build guardrails that make retreat heavier than continuation.

Guardrails are not punishments. They are asymmetries.

Breaking the new pattern should cost more than keeping it. Not infinitely more. Just enough that on a mediocre day, when motivation is low and old habits are calling, the path of least resistance runs through the new pattern, not around it.

At Mu’ta, Khalid made retreat survivable for his own forces and expensive for Byzantine pursuit. Asymmetric friction. The right choice was also the easier choice. At Yarmouk, the Muslim center held not because of superior courage but because the social cost of running past your own family was unbearable. That’s a guardrail made of shame and witness.

Your equivalent might be: bylaws that require a supermajority to undo. Infrastructure changes that would cost millions to reverse. Social commitments that make backsliding visible and costly.

The test is simple: when enthusiasm dips, does the system still hold? If it only survives on peak motivation, you have not built guardrails. You have built a cult.

You give people focal points so they can coordinate without constant instruction.

You cannot run a permanent system on heroic communication effort. It has to coordinate itself.

Schelling’s lesson is simple: if there is an obvious when and where, people can find each other without orders. The prayer schedule in early Islam was one such device. Your equivalent might be a fixed weekly time band and place where the work of your change happens, plus a simple ritual that marks its beginning. If your people have to ask “when do we act?” every time, you have not built a focal point. You have built a messaging problem.

You plan as if incumbents will quietly add sludge to your channels.

The existing system will not ignore you once you matter. It will respond not just with arguments, but with friction: extra forms, slightly worse interfaces, permit delays, cost increases, reputational pressure. So you shelter your growth phase in pockets it does not watch closely, and you refine your pattern there until it can survive open pressure.

You watch tempo: shorten your own cycles, lengthen theirs.

This is Boyd’s lesson, and it applies beyond battlefields.

The side that cycles through Observe–Orient–Decide–Act faster gains the advantage. The side that can disrupt the other’s cycle (through ambiguity, friction, overload) gains even more.

For your own system: fast feedback, clear decision rights, protected slots where people can act without asking permission.

For the incumbent you’re trying to displace: opacity about your next moves, unpredictable timing, pressure that shifts faster than they can coordinate a response.

At Yarmouk, Khalid kept his information flowing and choked Byzantine intelligence. He applied arrhythmic pressure—hit, pull back, let them start to stabilize, hit somewhere else. They never settled into a rhythm.

Your equivalent depends on your arena. But the principle is the same: make your own decision cycle fast and reliable. Make theirs slow and uncertain.

Behind each of these moves is something less fashionable than “disruption”: patience with structure. The willingness to spend years on the carpentry of defaults, guardrails, scaffolds, and signals.

The first essay, #62 showed why willpower loses to gradients.

This one is about what it would mean to stop sending people into battle naked. In Sun Tzu’s language, permanent change ends up being nothing more and nothing less than this:

Choose your ground with care.

Know the real Way your system serves today, the Heaven that sets its cycles, the Earth that shapes its paths, the Commanders who actually decide, and the Method that carries weight week after week.Secure your supply.

Build scaffolds that feed the new pattern until it can stand. Protect the fragile phase from full contact with the old riverbed.Build your signals.

Set focal points in time and space. Make “when we move” and “where we rally” into common knowledge that does not depend on constant messaging.Raise the cost of the enemy’s favorite moves.

Whether the enemy is an external incumbent or the gravity of your own old habits, design asymmetries. Make its easy road harder. Make your hard road easier.Then let repetition, friction, and terrain do what speeches cannot.

Commanders from Sun Tzu to Khalid to Boyd understood this. Strategy is nothing mystical. It is the shaping of roads and rhythms so that, when the moment comes, people almost cannot help but move the way you designed.

Most who talk about change still behave as if roads are given and only stories are negotiable. They write manifestos, give keynotes, and trend for a day. Then the world listens politely, nods, and keeps walking the same paths. If you want different outcomes, you do not just tell people to walk somewhere else.

You move the roads.

Everything else, however noble, is commentary.

In the next essay, we will dive into Khalid’s grammar and case studies. Stay tuned.

References

Akram, A. I. (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Walid, His Life and Campaigns. Karachi: Ferozsons.

Alter, A. (2017). Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. New York: Penguin.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tierney, J. (2011). Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. New York: Penguin.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Boyd, J. R. (2018). A Discourse on Winning and Losing. Maxwell AFB: Air University Press (posthumous compilation of Boyd’s briefings).

Donner, F. M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503.

Hagger, M. S., et al. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 495–525.

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338–1339.

Kaegi, W. E. (1992). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kouchaki, M., & Smith, I. H. (2014). The morning morality effect. Psychological Science, 25(1), 95–102.

Milkman, K. L., et al. (2021). A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging physical activity. Nature, 600, 356–361.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sunstein, C. R. (2019). Sludge: What Stops Us from Getting Things Done and What to Do About It. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sun Tzu. (1994). The Art of War, trans. R. Sawyer. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: PublicAffairs.

This is fascinating! I’d love to apply these 5 constant factors to lifestyle/health pursuits